Working Anyway: On Physical Challenges – Reflections from a Retiree

Chances are, right now you are in pretty good health, and maybe aging or physical difficulties are something you think may not happen until decades from now… and I truly hope this is the case. But most women are working on into their early seventies and further, in order to save enough for a comfortable retirement. Even in our sixties, our bodies start to slow down and respond differently, and problems like arthritis might sneak in.

I’ve been physically handicapped nearly all my life. I had polio at age three in 1951, and emerged from six months in a rehab facility with a partially paralyzed, atrophied leg and fully paralyzed foot, a brace and little arm-cuff crutches. My weaker leg grew slowly and never became a fully developed leg, which is common with paralytic polio. Eventually I could walk without the assistive devices, then started needing similar strategies again in my fifties.

With this challenge, I was not able to do jobs like waitressing, teaching, nursing, sales or any type of work requiring standing. I could not be on my feet constantly for more than a few minutes without my leg collapsing. My mother had always implied that she was afraid I would be dependent upon her all of my life and encouraged my getting a college degree in art.

Originally, I wanted to be an artist. I attended three years of art school at two California colleges, and then ran out of money and realized that commercial artists (before personal computers) had to live in big cities, which were not my cup of tea. I quit college temporarily in 1969, disappointing my mother. I became a seamstress, a factory worker, and then a cost estimator. This last field led me to the slightly naïve assumption that I’d like to be an accountant. I had researched professions that were needed everywhere in which men’s and women’s starting salaries were similar. Then I went back to college for two years in 1975, working full-to-part time and taking a full unit load, and slogged through the dry, complicated material that was so foreign to me. I got my BA, and always had work as a result. (Mom still regretted this vocational choice, despite my valor in re-educating myself in a career in which I could actually make some money. It’s sometimes not easy to meet our parents’ expectations.)

In auditing class, my instructor looked right at me when he told us that if we worked for what were then called “the Big Eight” accounting firms, they were discriminatory and tended not to hire anyone who was… well, not white, and/or “different.” He told us that women would not be able to wear pants to the office (in 1977) nor could anyone bring a brown bag lunch. Anything less than three-piece suits and eating with colleagues at local cafes was frowned upon. And I knew he was trying to tell me that a two-inch limp was not going to be acceptable. I did interview with a couple of those firms and was never sure if it was my gimpy leg, totally visible when wearing a skirt, or the fact that I was a B rather than an A student, that caused them not to hire me. (I’d been relieved to hear from one prospective employer that B students were more desirable than A students due to our being less idealistic and having interests other than school.)

I worked full-time for nearly forty years as soon as I finished college and part-time after “retirement.” So much for the concept many people have that handicapped or disabled people don’t work, and similarly, the mistaken idea that handicapped people get some kind of government aid. I had a new housemate at one time who asked me how she could get on public assistance with her “bad” knee, thinking I’d know all about that. I was a little taken aback, and didn’t know where she would begin, especially with such a minor issue. Most of the polio survivors I know have had full careers (and no governmental aid). We tend to be highly educated, with many or most in professional work, and we also are often described as “type A” personalities or over-achievers. Many of us were taught that we would have to try harder than others in all endeavors, since we had a disability to make up for.

In the long run, working for CPA’s and then starting my own tax and bookkeeping service served me well. Although tax work was grueling for five months of the year, with ridiculously long hours, it was satisfying from a puzzle-solving point of view. I could also partially set my own hours in the other months (important for a person who has fatigue issues), and found that I loved most of my clients and enjoyed unravelling their tax and accounting problems. I felt useful and valued.

With a handicap, it’s particularly important that if we work for someone other than ourselves, we’re able to get accommodation and understanding of our limitations. This may be as simple as the right desk arrangement, or only working in a place that has an elevator, or as risky or difficult as negotiating for shorter hours so that we can do our best work without exhausting ourselves. At times, we may be passed up for promotions or thought less of because we don’t look, walk or talk the way most people do (as is often the case with able-bodied women in the workplace). Thankfully the Americans for Disabilities Act was passed in the early 1990’s, so technically, it’s illegal to discriminate solely for a handicap now.

I think it is important to make sure that employers know how valuable our contributions are in the workplace, and exactly what they are, especially if we are asking for concessions such as reduced hours. But I’ve known handicapped people who needed their jobs enough that they put up with a lot of difficulty, such as flights of stairs or long hours that left them far more fatigued than a normal person at day’s end or the weekend. On the other hand, if a woman has the entrepreneurial spirit, any self-employment that showcases a physically realistic skill can be good, especially if it’s well-paid work. Although marketing oneself can be the biggest challenge, if the business produces a living income, this can be the way to be able to design hours and work habits that also support health.

Age discrimination can be tied in some ways to physical disability, but even without a handicap, I’ve known women who were essentially forced out of their jobs when they neared the minimum age for collecting Social Security, at a time when they had planned to keep working to increase their savings. Finding work as a woman over fifty can be challenging unless you’re willing to do something for lower pay (which can be a pleasant alternative if the stress is also less). See this Ms Career Girl article – it can be done!

Many physically handicapped people will do well in some type of desk work. I’d recommend computer programming, scientific work, editing or something in a related field, because there’s more money there than in most other desk jobs that don’t require a lot of travel or physical stress. But administration, management or customer service can also be well-paid and satisfactory. (I’m leaving out legal work because it’s so stressful, generally.) And usually with a handicap, we have higher medical costs, so a mid-low salary can put us in a position close to poverty.

Like Mom, I do have a modicum of wistful regret that I did not do something more creative for most of my life, but I also know that the artistic arena can be dauntingly competitive. I had thought that at some point I’d become, for instance, the CEO or director of a non-profit that brought children to the arts—but that would still have been an administrative position.

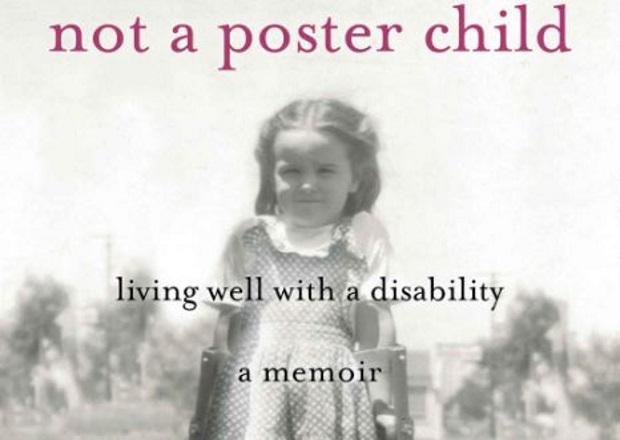

So here I am, late in life, almost seventy-one, having written a book post-retirement that has met with critical acclaim (Not a Poster Child: Living Well with a Disability – A Memoir). I would never have guessed decades ago that this would happen, and it’s been an exciting change.

It’s wonderful to have a career that you love. As my husband says, he was fortunate to have a passion that paid (computer programming and high-tech problem solving). But I don’t know that most people are able to accomplish that. I think that any woman who finds work that is stimulating, and likes the people she works with, and makes enough to support herself, has actually had a very successful career. I count myself among those women!

This guest post was authored by Francine Falk-Allen

Francine Falk-Allen was born in Los Angeles, had polio at age three, was hospitalized with paralysis for six months, and has lived nearly all of her life in northern California. As a former art major who got a BA in managerial accounting and ran her own business for thirty-three years, she has always craved creative outlets. This has taken the form of singing and recording with various groups, painting, and writing songs, poetry and essays, some of which have been published. Falk-Allen facilitates Polio Survivors of Marin County, and a Meetup writing group, Just Write Marin County. She was the polio representative interviewed in a PBS/Nobel Prize Media film, The War Against Microbes. She loves the outdoors, gardening, pool exercise, her two silly cats, spending time with good friends and her husband, Richard Falk, strong British tea, and a little champagne now and then.

www.FrancineFalk-Allen.com Facebook: Francine Falk-Allen, Author

Not a Poster Child: Living Well with a Disability – A Memoir will debut officially on August 7, 2018 and is available to order now at shewritespress, your local bookstore or www.Indiebound.org (which channels funds to local bookstores), www.barnesandnoble.com, or Amazon.