Letting Your Imagination Go Crazy Or Outlining And Organizing

Number four in a series of twelve

To outline, or not to outline, that is the question.

The other question is: How many pieces of chocolate in one day is one piece too many? Five? Ten?

But, alas, I digress.

Let’s talk about outlining your book…or not.

I don’t outline when I write my books. I write a general synopsis for my editor and agent, the two wise men, to look over. We go back and forth, editing and deleting ideas and characters, and I start writing as soon as I know the first sentence of my book.

My mind then starts to open like an old, cranky, and creaky door.

Here’s an example of the synopsis that I wrote for What I Remember Most:

Grenadine Scotch Wild. Thirties. Auburn hair. Light green eyes. Wiry.

Setting: Sisters, Oregon (town will be re-named). Small town, western style buildings, surrounded by snowy mountain peaks.

Grenadine has been in foster care since she was five years old. Her back story in foster care will be told through reports from CSD, teachers’ comments on report cards, police reports, and hospital/doctor charts.

Grenadine cannot remember what happened to her parents the night they “disappeared.” She remembers them as being kind and loving, her mother engaging her in art projects with paints, feathers, and beads, her father teaching her how to draw. As an adult, she realizes that her parents were very young, hippies, free living. They lived in a tent, the back of a VW van, communes, a true vagabond lifestyle.

She hears the words, “Run, Grenadine, run!” off and on, her whole life. She knows it’s her parents. She can hear their horror and panic. She cannot remember what happened before they insisted she run.

Grenadine is dyslexic. She became a painter and collage artist…

You get the idea. The synopsis is about two pages long. I describe how Grenadine’s life has collapsed (she’s been arrested for a crime she didn’t commit), how she’s going to fix it, the struggles she’ll have, and the other characters she’ll come into contact with until we have our resolutions.

A synopsis is different than an outline. A synopsis is ideas and thoughts for a story. An outline is much more precise in terms of goals for each chapter.

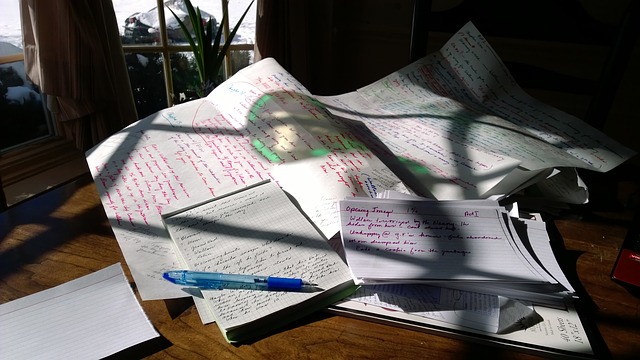

I can’t write, or stick to, an outline. I can’t write a chapter by chapter summation as I don’t know what’s going to happen next until I get there. I can’t chart sub plots and plot points and arcs because they are a mystery to me.

Following an outline would feel like I was writing in a straight jacket. It would feel too restrictive, as if I couldn’t take the story straight off a cliff if I wanted.

It would make me feel weird, like this odd book person.

My story will not reflect some, or much, of the initial synopsis when the book is done anyhow. I might not include a character I initially included. The ending might be completely different. The personalities and issues change.

The theme of the book comes to light. I add humor and tears I hadn’t planned on. I’m sure it drives my editor and agent crazy, but I can’t always stick to the plan.

That about sums up my life: I can’t always stick to the plan.

Many writers write like me. They have a vague idea, a character forming, problems and conflicts bubbling to the surface of their brains, an image, and they start writing away.

They take their imaginations on a ride and fly off with them, writing each scene as it leaps into their heads, sometimes writing scenes far ahead in the book, then back tracking.

But we women write differently, just like we wear different kinds of clothes.

Some writers like to have every chapter planned out, from who is in the chapter, what they say and do, and how it moves the book forward.

Every character is fully described in a notebook from birth to death. They know the characters’ arcs, the sub plots, the minor characters, and the issues and themes BEFORE they start writing the book.

It’s all mapped out in detail, the information is applied to the outline, and they stick to that sucker, with some adjustments along the way.

The story is organized and ready to go charging towards the climax and resolution.

The advantages in using this strategy are blindingly easy to see. You simply head off a bucketful of problems in plot/characters/climax/etc. and your story line is clear from the beginning.

I wish I could outline as I think it would save me a TON of time and hair pulling frustration.

But ya gotta find what works for you, friends. Outlining a book, or not, is personality driven.

Need more advice on whether or not to outline your book? Let’s hear from writers smarter than me.

Catherine Ryan Hyde: I liken my process to a multi-day car trip. I have some idea where I’m going, and what roads lead there. Otherwise I risk ending up nowhere. But I also don’t want to make too detailed a plan (For example, I’ll drive X number of hours and then stop at this motel at this time.) because I risk blowing right by Carlsbad Caverns or the giant meteor crater because they’re not in my notes. So I leave a little more room in the middle, for opportunities I couldn’t possibly have seen coming when I left home.

Barbara Claypole White: I’m an organic writer, with a brain that feeds on instinct and research. I love to meander and rewrite and excavate endlessly. However, writing to contract has taught me the value of a road map, and now I create story boards written to movie beats. I guess that means I’m a hybrid.

Kristina McMorris: For all of my books, I create a board of mini-Post-its that each represent a chapter. I’ll simply jot down a few notes summarizing the purposes of the scenes, which helps me confirm that every one of them is essential to the story. Writing The Pieces We Keep, I used this particular plotting board and found the visual layout especially handy in juggling dual timelines interwoven with mystery elements. Plus, as a person who enjoys crossing tasks off my to-do lists, I always love being able to move the Post-its upward on the board as I complete each chapter, assuring me that I’m indeed nearing that ever-daunting finish line.

Jo-Ann Mapson: Usually what comes to me first is an image. Like Margaret in Blue rodeo, who is first seen in the book wearing red underpants and a work shirt and trying to cup water in her hands to break up the dog who’s having sex with her dog while Owen, a sheepherder, is watching from his horse. I pretty much always start writing toward the image that seems to be emblematic of my story. I have an outline I made up that is more like a story problem. I write down the events, the hidden stories that made the character who she or he is, and in pencil, so I can move things around.

Laura Drake: I have a character, with a flaw. I have a first scene, and a vague idea of where I’m going. Then I take a leap of faith and begin. I don’t think it’s the easiest way. My brain doesn’t care.

Kimberly Belle: I start with a fairly detailed outline, though it’s fluid and I always end up surprising myself along the way. Characters pop up uninvited. The plot makes turns I wasn’t expecting. But I do like to know where I’m going and a pretty decent idea of how I’ll get there, otherwise I end up writing myself into corners.

Marie Bostwick: The time I invest up front in outlining, and I do spend at least a couple of weeks doing so, saves me time and anxiety in the long run because I understand the arc of the story more completely as well as the personality and motivation of the characters. It makes the characters more real to me and, ultimately, to my readers. However, I never let myself become so tied to my outline that I don’t leave room for changes. I’ve never written a book that didn’t change, sometimes markedly, from outline to final draft.

Kimberly Brock: My process starts like an excavation of a setting and time, because I’ve stumbled across something unusual that interests me. Especially, I like to discover something I know nothing about, but maybe should have known. Something obscure that fascinates me. That starts a story for me with setting, historical fact and metaphor. I fill a notebook with what some people call Mindmapping and those ideas deliver characters to me. From there, I write the first chapters and see where they start to take me and I always, always write my resolution before I go any further. THEN I sort of scaffold the framework of the story arc and finish a first draft.